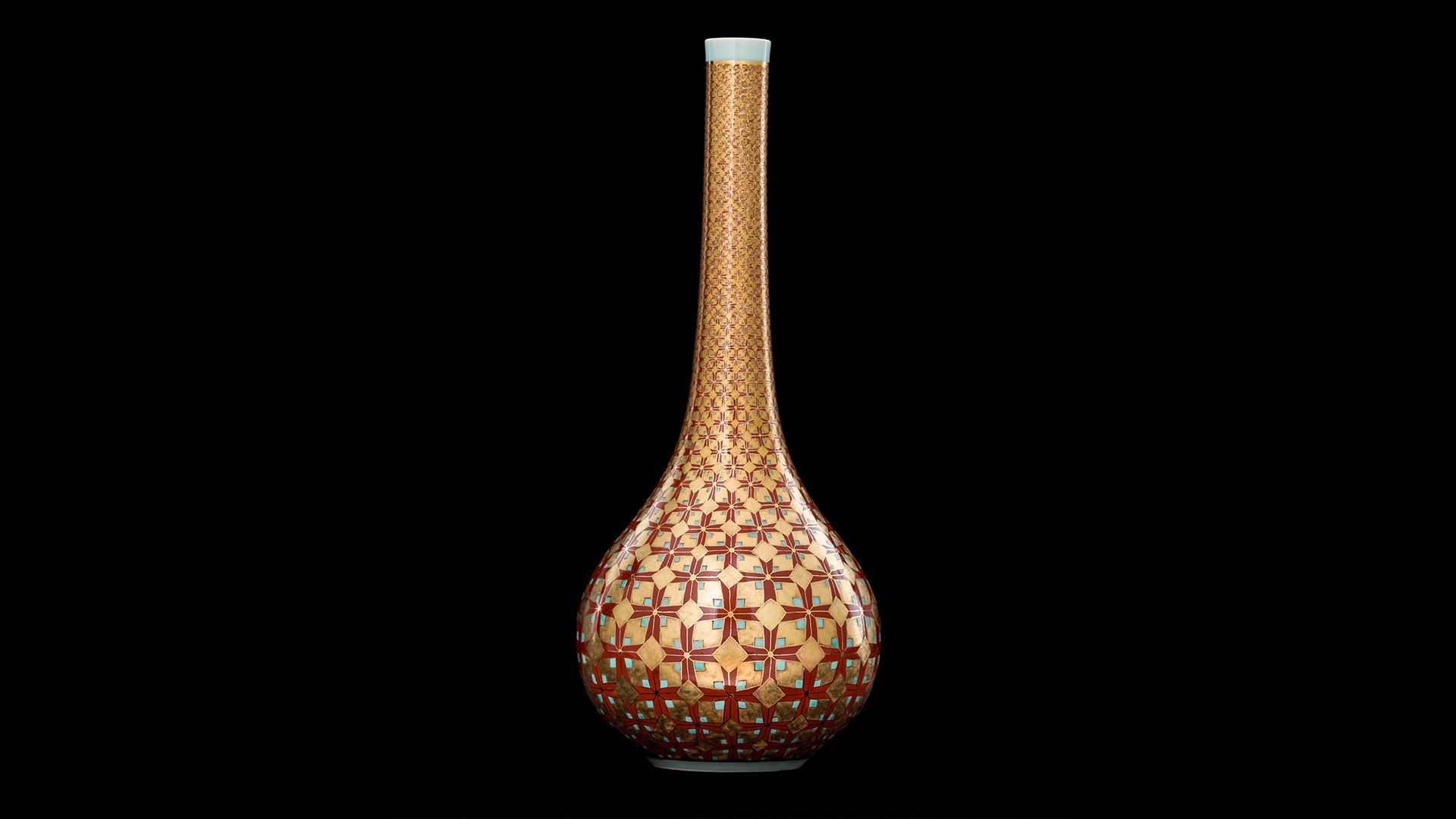

A few years ago, I was moved to tears by a First People’s exhibition,

“The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I was struck, not just by the beauty and loving patience emanating from the work,

but also by the fact that its aim was to capture the intangible magic of the phenomenal

world within the tribe—to bring it “down” or “out”—to make it palpable and to inscribe

it on objects in order to empower everyday life. For the people using the objects,

these instruments of daily life forged connections, gave meaning,and established a

sense of place. A cradleboard for the papoose, for example, was emblazoned with everything

splendid the mother could invite: the sun, the moon, the stars, the animals as sacred.

This is not “deco.” It’s invocation. It gives the child the world; it serves as

protection and empowerment. A technique in traditional Japanese garden design is

“to capture alive.” It means to capture not the surface, but rather the life force: the

vital essence animating the physical. In the same way, these objects captured the

“spirit world”—the spiritual world, which is alive and taps into the virtue inherent in

sense objects and sensory fields, the worthwhileness of being. To my mind, this was not

“art” in the conventional sense, but part of the tradition of “power objects,” conjoining

functional and spiritual purpose. These contemplations inform my work.

Gina Stick, 2018